Series Overview: Hi, my name is Shari and like the majority of our readers I don’t have a degree in science. What I do have is almost a decade of experience working closely with Genetic Counselors, and a passion for sharing genomic information in an approachable and easy to understand way. This passion was developed early in my career, fueled by my quickly building frustration about the over-complicated resources I found during initial attempts at self-guided learning. Genomics 101 is a blog series by GenomicMD that aims to be a solution to that frustration for others. By breaking down the complex language surrounding this field, we hope to empower people (like you!) to be more informed about how genomics can affect their healthcare journey.

Welcome to another chapter of Genomics 101 – an ongoing blog series by GenomicMD designed to break down the complicated language surrounding DNA and help people (like you!) truly understand how genomics impacts your health. In our first post we used an encyclopedia analogy to describe DNA, and defined terms such as genes, chromosomes, base pairs, and genomics. This post will dive into some of the most commonly used and frequently misunderstood words in genomics: ‘genotype’ and ‘phenotype,’ and explain the difference between genetic and environmental risk – hopefully in a way that both helps you apply it to your own life and doesn’t bore you too much. Let’s get started!

When discussing genetic or genomic testing, you often hear medical professionals throwing around the terms “genotype” and “phenotype” - but what do these words really mean? Genotype is a bit easier to understand in the context of the conversation, as it already contains the word “gene”. Based on context clues we can assume that genotype means the combination of genes that an organism has inherited from its parents – or its “type” of “genes.” However, the meaning of the word phenotype is a little bit harder to work out if you don’t have a good base knowledge of ancient Greek (If you do, can we be friends? I have a lot of etymology questions to ask you!) To put it plainly, an organism's phenotype is its observable traits, which are created from a complex relationship between its genotype and its environment. So whereas your genotype is the internal written instructions for building your body that no one can see (without an expensive magnifying glass), your phenotype would be things like your physical appearance or behavior.

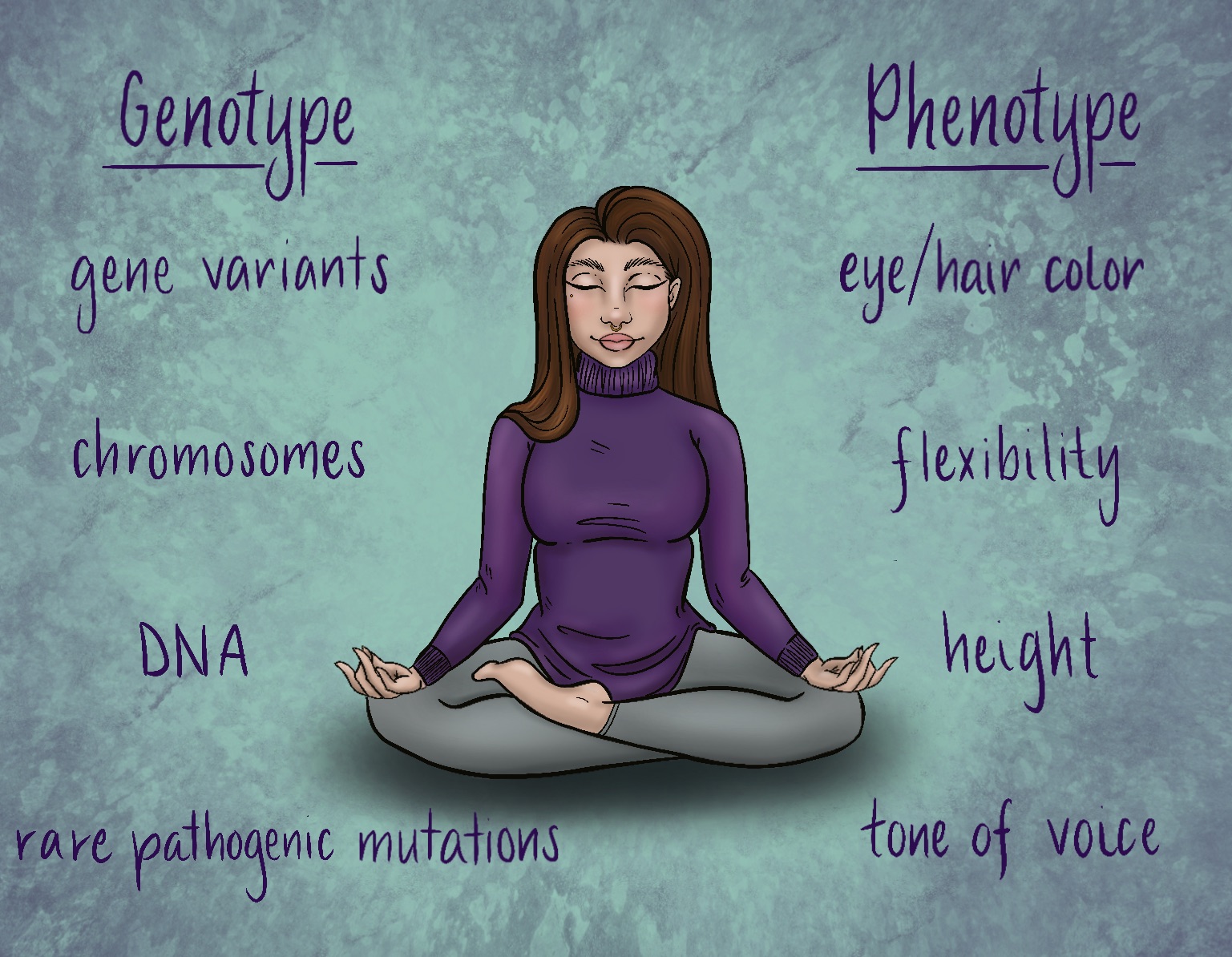

The term phenotype can often be a bit trickier to understand than genotype because, as noted above, these traits come from a complex relationship between your genes AND your environment. This means that your genes can determine some parts of your physical traits (like your eye color, height, or natural hair color) but some traits are also shaped by the world around you or your lifestyle – such as your weight or flexibility. For a simple example of this complex relationship: a person’s genotype can write instructions for the size and shape of their hands–but their environment (playing guitar or otherwise working with their hands a lot) could create calluses on them. Check the graphic below for a visual breakdown of some genotypic and phenotypic traits, which we will explain further in the next few paragraphs:

So how does this all play into your risk for developing certain diseases? Well, risks generally fall under two main categories: environmental and genetic. Environmental risks are those that can be impacted by your surroundings or lifestyle – such as being exposed to pollution or chemicals that can make you sick, or taking part in unhealthy activities. Most people know of a few things that increase the risk of disease, like how smoking can increase the chance to develop lung disease, drinking can increase the chance to develop liver disease, and over-eating foods high in fat and cholesterol can increase the chance to develop heart disease. These facts are well-known and mentioned regularly in literature and media – and they are all examples of environmental risks that we often have control over. Genetic risks, on the other hand, are those associated with certain changes in our genetic code called “mutations” or “variants,” and these genetic changes stick with us throughout our lives.

It’s important to know that not all mutations are ‘bad’ or cause health problems – every person has thousands and thousands of variations in their genetic code that make us who we are. The vast majority of these genetic changes are harmless and simply account for unique traits like our eye color or shoe size, but certainly more rare genetic changes (like mutations in genes like BRCA1 and BRCA2, most known for their impact on breast cancer risk) can be pathogenic, or harmful. Many people choose to take genetic tests in order to learn more about these inherited risk factors. Knowing about one’s personal genetic risk is helpful because although they are unchangeable, understanding what they are allows people the opportunity to pay closer attention to specific environmental risk factors – empowering them to make conscious decisions (like earlier or more frequent screenings for disease) that help increase their likelihood of living long and healthy lives.

Let’s use an analogy to break all of this information down (I love a good analogy!) Imagine for a moment that we are baking a gingerbread person. The recipe itself would be the gingerbread person’s genotype–the set of instructions that show us how to bake everything to a specific standard. This means that if we follow the ingredients and instructions exactly the way they are written we would end up with the same gingerbread person every single time. Keeping this in mind, there are some things in every recipe that can be altered without negatively affecting the outcome, such as swapping out decorations or a few spices. For example, if we wanted to change out nutmeg for some extra cinnamon or add a little bit of clove or allspice to the mix, we would definitely change the outcome of our cookie person–just like a genetic mutation changes our genetic code. This wouldn’t necessarily alter the outcome of the cookie in a bad way, though. It would just make it different from the reference gingerbread recipe we started with.

We may not be able to say the same thing if we decided to swap out all of the spices for salt, though. This sort of ingredient difference may cause difficulties down the line when we serve our gingerbread recipe to family and friends-kind of how a pathogenic mutation in a family can sometimes cause health problems down the genetic line. We can also affect the cookies ‘environmental risk’ as well. If the standard recipe calls for baking our gingerbread person for 30 minutes at 350 degrees we could possibly get away with leaving them in the oven for 35 minutes if we are too busy to grab them when the timer goes off, but I imagine that we would take out a much different and probably inedible cookie if we accidentally cranked the heat up to 400 and forgot them for 45 minutes.

These same concepts apply to people with regards to environmental and genetic risks. Humans can survive in all types of environments making all types of choices, but the risks we choose to take can make a difference in the outcome of our lives and health. This all goes to say that though the standard genotype is a great ‘recipe’ for creating a human being, there are lots of variations to that recipe and additional environmental choices we can make that cause little harm to the core of who we are. It's the pathogenic changes and dangerous environmental risks we need to worry about! We hope this post was able to help add clarity to some of the more complicated language surrounding genotype, phenotype, and risk. Please join us for the next post in our Genomics 101 series, where we will do a deep dive into the history of heredity (how we pass genetic information down from parent to child) and the ‘father’ of genetics–Gregor Mendel.

Blog Glossary:

Genotype - the combination of all of the genes that an organism has inherited from its parents – or its “type” of “genes”

Phenotype - an organism’s trait(s), sometimes visible such as physical appearance and behaviors, and sometimes not such as the risk of disease. An organism’s phenotype is created by a combination of its genes AND environment.

Genetic Risks - risks associated with certain harmful genetic “mutations” or “variants”

Mutations/Variants - changes in our genetic code. Everyone has thousands of variants and/or mutations in their genetic code that make us all unique. Most of these changes are harmless-–like those which account for eye color or shoe size.

Pathogenic Mutations/Variants - harmful genetic changes like certain well-known mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 that increase the likelihood of certain cancers.

Environmental Risks - risks that can be impacted by your surroundings or lifestyle – such as being exposed to chemicals that can make you sick, or taking part in unhealthy activities like smoking.